We often refer to older adults as exhibiting memory impairments, or reduced memory specificity. In fact, it can be difficult to try and convince anyone otherwise. But is this an accurate portrayal? In this blog post I want to discuss the implications of such sweeping statements, and whether they are justified by the available data.

First, some thoughts based on anecdotal evidence.

Older adults themselves often complain that their memory “isn’t what it used to be”, or that they are “forgetting things more and more” as they get older. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve had this conversation, both with older adult participants in my studies, and with older adults I know socially. In fact, I’ve had the same conversations many times with people who are much younger – people in their 30s, 40s, and 50s. When I ask them about the type of memory failures they have experienced, people usually tell me that they forget the names of famous people, or that they walk into a room and forget why they went there. These kinds of memory failures happen to everyone; they may become more common as we get older, but they are certainly not restricted to people over a certain age.

I can’t remember a single instance in which a healthy adult, of any age, has told me that they have trouble remembering events and experiences after they have happened.

Ageing memory in the lab

Yet this is exactly what we find when we measure older adults’ autobiographical memories in the lab. We find that their memories are less detailed than those of younger adults (e.g. Levine et al., 2002), or that they tend to recall general memories that are composites of either semantically similar, or temporally proximate, experiences, rather than descriptions of specific one-off events (e.g. Piolino et al., 2006).

This dovetails neatly with the deficits we find when we ask older adults to remember lists of words they learned a few minutes earlier (Clarys et al., 2009; Craik & McDowd, 1987; Nyberg et al., 1996), to remember their way around a virtual environment (Yamamoto & DeGirolamo, 2012), or to remember the associations between pictures that were presented and the locations on the computer screen in which they appeared (Siegel & Castel, 2018).

In short, together these findings suggest that older adults simply don’t remember as well as younger adults.

When stated like this (as it is in much of the published research showing age-related memory deficits), it sounds as though older adults are unable to recall detailed or specific memories.

This is not true.

In most studies of autobiographical memory, participants are asked to recall several different memories, and their scores are derived from averaging what they recalled across the whole set. Yes, on average they may remember fewer details than younger adults, but within the set of memories there are likely to be some that are very well-remembered and some that are not well-remembered at all (more on that in a later post).

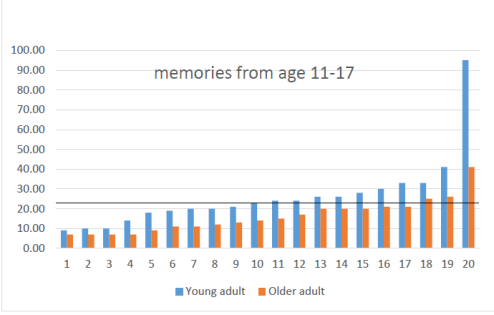

The graph below shows the number of episodic (event-specific) memory details recalled (y-axis) by older and younger adults when we asked them to recall a single memory from between the ages of 11 and 17 (the x-axis represents the 20 participants in each group, ranked, within group, in order of lowest to highest episodic memory score).

The black reference line shows the median score for young adults. Older adults certainly seem to recall fewer details, but let’s not forget that their memories are somewhere between 48 and 69 years old. Younger adults’ memories are much younger – between 2 and 19 years old. That’s not a fair test.

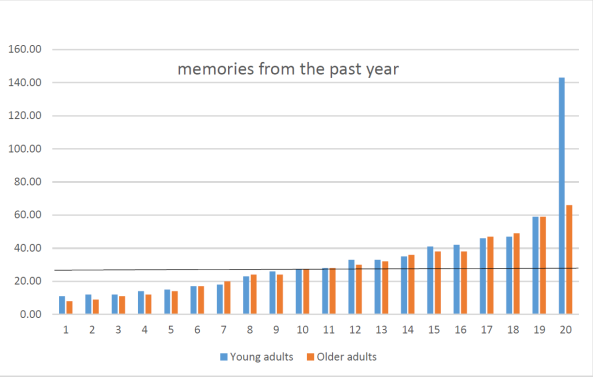

This next graph shows the number of episodic details recalled by the same participants (not in the same order), this time when asked to recall a memory from the past year. This time their memories are roughly the same age.

The top-performing young adult remembered more than twice as many details as the top-performing older adult… but also more than twice as many details as the second-best young adult. This person’s data point is an outlier – it is more than 3 standard deviations above the young adult average score. The individual who produced this score was recalling something that was clearly exceptionally memorable. It was NOT the same person who recalled the most details in the memory from age 11-17. Aside from this individual, younger adults don’t look any better than older adults on this task.

Whether we mean to or not, we tend to talk about memory performance as though it is a trait, and we rarely discuss the interaction between a person’s memory ability and other factors – how long ago the event happened, or how inherently memorable it was. It would be absurd to suggest that last Tuesday’s breakfast should be remembered in as much detail as your wedding day, or the birth of your first child. Indeed, as far as I’m aware, no one is suggesting that, but we aren’t really talking about (or formally investigating) these issues either.

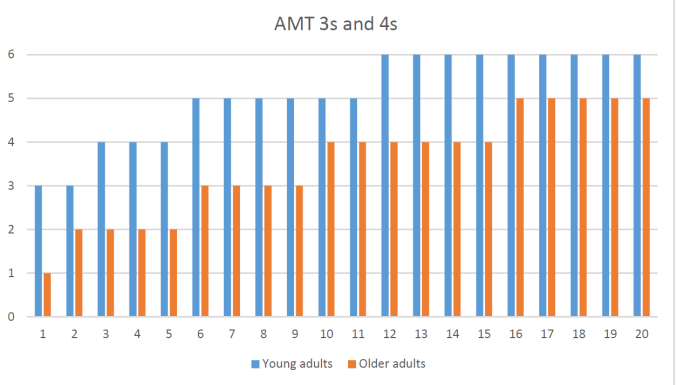

If you’re trying to prove that older adults’ memory is impaired, one of the most reliable autobiographical memory tasks is the Autobiographical Memory Test. In this task, participants are given a cue word, and asked to recall a memory associated with that word. They are asked to recall a specific, one-off memory that lasted a day or less. The memories that participants report are scored on a scale of 0 (no memory) through 1 and 2 (memory of a repeated event or an event that lasted longer than 24 hours, with or without detail), to 3 and 4 (memory of a specific event with or without detail). Typically, participants are given a list of words, and attempt to recall a different memory associated with each, and their score is the average specificity rating of all the recalled memories.

We did this with the same participants as above. Young adults scored, on average 3.43 out of 4 (SD=.56), while older adults scored an average of 2.60 (SD=.54). This difference was highly statistically significant. The averages we calculated were across 20 participants in each group, and across 6 memories per participant. According to this analysis, older adults’ autobiographical memory is impaired – again, this suggests they are unable to remember as well as younger adults.

Let’s look at the results another way. Here are the 20 younger and 20 older participants in rank order, with the y-axis representing the number of memories (out of 6) for which they scored 3 or 4 points (i.e. specific memories with or without detail).

It’s clear that a greater number of young adults’ memories score 3 or 4 points, but note that every single participant recalls at least one such memory, and the vast majority of people recall several. Older adults are not unable to recall specific memories – they are perfectly able. They just do so less frequently than younger adults.

The question of why is another matter. I don’t know of any studies that have attempted to understand how participants approach this task. When faced with the requirement to recall any memory, from any time period, that may be only loosely associated with a generic cue word (e.g. happy), how do people engage in the the kind of mental search that will result in the recall of an appropriate memory? We tried some very brief and informal investigations, asking people to think aloud when they were given the cue word – for the word happy, people tried to think of “the happiest I have ever been”, or “the first time I remember being really happy”. Whether this is consistent with what researchers think is happening, I don’t know. It’s also quite feasible that this task could be approached differently by older and younger adults, particularly given that older adults have to search a much larger set of accrued experiences.

What’s clear is that autobiographical memory is more complex than we usually like to admit, and that when we think we are measuring autobiographical memory ability, if we ignore the features of the events we ask them to describe, then we may be doing nothing of the sort.